This is the second blog in our series directed at young budding enthusiasts. In this, the train, writing in first person, tells the readers of the bridges and viaducts that are an important part of any rail network.

I am sure all of you know what a bridge is, but may not be too sure what a viaduct means. Briefly, a viaduct is a long bridge-like structure carrying a road or railway across a valley or other low ground. Today, I am going to tell you about both, bridges and viaducts, that are built for me to cross rivers and other expanses of water, to negotiate valleys and handle undulations in the terrain.

Why do we need bridges or viaducts? Unfortunately, the land is seldom unobstructed, level or straight. It goes up and down, it undulates, it is criss-crossed by streams and rivers as well as shallow or deep valleys. Unlike a road vehicle, that run on rubber tyres in most cases, my wheels are made of steel and they run on steel rails. The result is that my wheels slip easily, which means that the gradient or the slope on which I run cannot be too steep.

Let me try and give you a few figures. Gradients are specified in the railways by figures like 1 in 100 going up or down. This means that for every 100 units of distance I move forward, the land ascends or descends by one unit. This can be expressed as a percentage as well. For instance, 1 in 100 grade is a 1% grade. Similarly, 1 in 40 is 2.5%. Most railway lines in India do not have a grade steeper than 1 in 100. In fact, in the plains, grades are normally 1 in 200 or even flatter. It is only in the mountain railways that there are steeper grades. But that will be a separate story I’ll tell you later when I will talk of negotiating grades steeper than even 1 in 15.

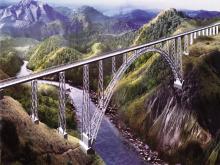

Thus, the track that I run on has to be more or less flat most of the time. Roads tend to follow the contours of the land they are on. Rail track cannot do that indiscriminately, so that whenever there is a depression in the land or a river valley, there is need to build a viaduct or a bridge. Bridges are normally built across rivers or arms of the sea; viaducts tend to cross valleys and low lying areas where there may or may not be a river.

Consequently, rail bridges and viaducts are as old as the railway itself. Obviously, there are all kinds, types and sizes of bridges. They could be only a few meters long or stretch for many kilometres. They could pass over the open sea or a mere slow flowing rivulet. Let us look at some of the types of bridges that I ply over in our country.

The oldest bridges that were built were arch bridges. These are based on the principle that an arch is a very stable structure. The span in Mumbai over which the first train ran in our country, the Dhapoorie viaduct, was an arch bridge. The arch bridge design reached its pinnacle on the Kalka-Shimla Narrow Gauge section where you can see a 4-tiered arch bridge, reminiscent of similar bridges built by the ancient Romans as aqueducts.

The screw pile bridge was another type of bridge the early engineers adopted particularly while bridging estuaries and backwaters where the current was not too severe. On the erstwhile Bombay Baroda and Central India Railway, it was this type of bridge that predominated between Bombay (now Mumbai) and Ahmedabad, including the Vasai creek, Mahi, Tapti and Narbada rivers. The bridge piers comprised of two or more cast iron piles that were screwed down to an appropriate depth where hard clay was found. While these bridges served the purpose at the time they were built, they had a short life and other limitations. The Indian Railways as a policy decided in 2001 to replace all such bridges.

The evolution of the well foundation adopted and pioneered by the early railway bridge designers and builders has been a major contribution to large bridge construction in the country. In view of the difficult subsoil conditions of the foundation bed, open foundations could not be applied in India in most cases. The advantages of the well foundation were quickly realized. This design was indigenous to India and had been adopted in early bridge and building construction apart from the construction of ordinary wells for drawing water. The well foundation involved the sinking of cylinders or wells of brickwork to considerable depths through the sand until clay or rock was reached. Piers were built over foundations of a single well or a cluster of wells. In many cases, even in the early years, the wells were strengthened with iron work consisting of both vertical and horizontal members. Once the wells were founded they were usually filled with sand and capped. The well foundation over time has become the most popular method of founding bridges in India.

You would have noted that in the case of the screw pile bridge and the well foundation bridge, you built piers, on which you had a superstructure. The latter normally consisted of iron or steel girders. As you travel on me through the country, you will come across various types and shape of girders. However, post Independence, particularly in the last three decades, there has been much greater use of pre-stressed concrete (PSC) slab girders and many of the new bridges built over major rivers either as replacement of earlier bridges or new bridges have been with PSC slab girders. Till the opening of the Boghibeel bridge in Assam, the Vallarpadam Bridge in Kochi was the longest bridge in India. It has 236 PSC girders, 198 of which are 40 metre long. The launching of girders, whether steel or PSC slabs, is a very exacting exercise and several alternative methodologies are adopted depending upon size of span, site conditions and accessibility of the site. These include use of cranes or derricks, end launching including the cantilever method, side slewing, use of trestles or with the help of a launching nose.

Many of the rivers, particularly in Northern and Eastern India are known to frequently change their course. Therefore, integral to the construction and maintenance of bridges is the need to ensure that the river flows in a well-defined channel and does not meander. For this, bridge engineers resort to the construction of bunds or walls to guide the water. These guide bunds can be a major construction as in the case of the bridge across the Brahmaputra at Bhogibeel near Dibrugarh in Upper Assam. The bunds built on the North and South bank are 2 kms. and 2.7 kms. long respectively, apart from about 16 kms. long dykes on each bank. Completed in 2018, this is the longest rail bridge in India with a length of 5.4 kms. Another feature of this bridge is that it is using welded steel with no rivets, the first of its kind on the Indian Railways. Like most other major rail bridges, this is a rail-cum-road bridge.

Railway Bridges are some of the ‘Mega Structures’ that have been created by railway engineers over the last hundred and sixty years. Many of these bridges are now over 100 years old and some need to be replaced. Across the Hooghly at Kolkata, the East Indian Railway built two noteworthy bridges known as the Jubilee (1887) and Wellington (Vivekanada) (1932) Bridges. A new bridge, the Sampreeti Setu, has been built in place of the Jubilee Bridge. Another remarkable bridge is the Pamban bridge which takes trains from the mainland to Rameswaram island in Southern India. This bridge, built in 1914, has a span that opens to allow ships to pass. Originally built for Meter Gauge, it was converted to Broad Gauge in the 1960s. Now under construction on the line from Jammu to Srinagar across the Chenab, an amazing Steel arch bridge is being constructed, which when completed, will be the tallest of its kind in the world with a height of 359 meters from the river bed level to the centre of the arch, five times the height of the Qutb Minar in New Delhi.

By the time the British left India, the rail network had reached almost every corner of the nation. The notable exceptions were the West coast and a link to the Kashmir Valley. The primary reason for this was the difficulty in building the large number of bridges and viaducts (and also tunnels) that would be required in both these regions. The Konkan line with about 2000 bridges has taken care of the West coast, while the link to the Kashmir Valley with over 750 bridges will be completed shortly after the bridge across the Chenab is ready.